Shifting the focus from viruses to bacteria

What happens to microorganisms in the winter? How does this alter the human microbiome? What kinds of immune responses and symptoms could this cause? WHY 0 COLD-LIKE SYMPTOMS WITH A KETOGENIC DIET?

While freezing temperatures do not always kill bacteria, they can limit or stop their growth. This means that the bacteria will not reproduce rapidly, but it will also not be fully killed. Listeria, for example, will cease growing fully in the refrigerator but will not die.

We use the languages and techniques at our disposal to try to explore and explain things. Science, in my opinion, is an inaccurate language since it is influenced by politics and is always evolving. There is currently no better way to describe matter. So, let’s go:

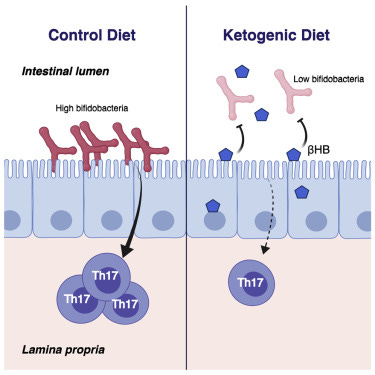

The role of Th17 cells in immunity is complex, and it is not accurate to categorize them as universally "better" or "worse" for immune function. Th17 cells play a critical role in defending against certain types of infections, particularly those caused by extracellular bacteria and fungi. They produce interleukin-17 (IL-17) and other pro-inflammatory cytokines, which help recruit immune cells to the site of infection and coordinate an immune response.

However, an excessive or dysregulated Th17 cell response can also contribute to the development of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Th17 cells are implicated in conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), multiple sclerosis (MS), psoriasis, and rheumatoid arthritis. In these cases, an overactive Th17 response can lead to chronic inflammation and tissue damage.

Thus, the balance and regulation of Th17 cells are crucial for immune homeostasis. In some contexts, a lower number or less activity of Th17 cells may be desirable to prevent excessive inflammation and autoimmune reactions. However, completely eliminating Th17 cells or suppressing them excessively can also have detrimental effects on immune defense against certain pathogens.

It's important to note that the immune system is highly complex, involving multiple cell types and mechanisms that interact and regulate each other. Th17 cells are just one component of this intricate network. Optimal immune function relies on a delicate balance and coordination between various immune cell types and their responses.

Overall, the significance of Th17 cells in immunity depends on the specific context and disease condition. Their activity and abundance need to be tightly regulated to maintain immune balance and prevent both inadequate and excessive immune responses.

Let’s look at the presented evidence:

Porcine gut microbiota in mediating host metabolic adaptation to cold stress

The gut microbiota plays a key role in host metabolic thermogenesis by activating UCP1 and increasing the browning process of white adipose tissue (WAT), especially in cold environments. However, the crosstalk between the gut microbiota and the host, which lacks functional UCP1, making them susceptible to cold stress, has rarely been illustrated. We used male piglets as a model to evaluate the host response to cold stress via the gut microbiota (four groups: room temperature group, n = 5; cold stress group, n = 5; cold stress group with antibiotics, n = 5; room temperature group with antibiotics, n = 3). We found that host thermogenesis and insulin resistance increased the levels of serum metabolites such as glycocholic acid (GCA) and glycochenodeoxycholate acid (GCDCA) and altered the compositions and functions of the cecal microbiota under cold stress. The gut microbiota was characterized by increased levels of Ruminococcaceae, Prevotellaceae, and Muribaculaceae under cold stress. We found that piglets subjected to cold stress had increased expression of genes related to bile acid and short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) metabolism in their liver and fat lipolysis genes in their fat. In addition, the fat lipolysis genes CLPS, PNLIPRP1, CPT1B, and UCP3 were significantly increased in the fat of piglets under cold stress. However, the use of antibiotics showed a weakened or strengthened cold tolerance phenotype, indicating that the gut microbiota plays important role in host thermogenesis. Our results demonstrate that the gut microbiota-blood-liver and fat axis may regulate thermogenesis during cold acclimation in piglets.

Bacterial adaptation to cold

Micro-organisms react to a rapid temperature downshift by triggering a physiological response to ensure survival in unfavourable conditions. Adaptation includes changes in membrane composition and in the translation and transcription machineries. The cold shock response leads to a growth block and overall repression of translation; however, there is the induction of a set of specific proteins that help to tune cell metabolism and readjust it to the new conditions. For a mesophile like E. coli, the adaptation process takes about 4 h. Although the bacterial cold shock response was discovered over two decades ago we are still far from understanding this process. In this review, we aim to describe current knowledge, focusing on the functions of RNA-interacting proteins and RNases involved in cold shock adaptation.

Effect of low temperature on microbial growth: lowered affinity for substrates limits growth at low temperature

At temperatures below their optimum for growth microorganisms will become increasingly unable to sequester substrates from their environment because of lowered affinity, exacerbating the anyway near-starvation conditions in many natural environments.

Reporting Key Features in Cold-Adapted Bacteria

Among the strategies used by cold-adapted microorganisms, a general well-known mechanism consists in the modification of cell membrane lipid composition, favoring shorter chains and decreasing lipid saturation [4] in order to maintain membrane fluidity while avoiding stiffness at low temperatures.

Advances in cold-adapted enzymes derived from microorganisms

Cold-adapted enzymes, produced in cold-adapted organisms, are a class of enzyme with catalytic activity at low temperatures, high temperature sensitivity, and the ability to adapt to cold stimulation. These enzymes are largely derived from animals, plants, and microorganisms in polar areas, mountains, and the deep sea. With the rapid development of modern biotechnology, cold-adapted enzymes have been implemented in human and other animal food production, the protection and restoration of environments, and fundamental biological research, among other areas. Cold-adapted enzymes derived from microorganisms have attracted much attention because of their short production cycles, high yield, and simple separation and purification, compared with cold-adapted enzymes derived from plants and animals. In this review we discuss various types of cold-adapted enzyme from cold-adapted microorganisms, along with associated applications, catalytic mechanisms, and molecular modification methods, to establish foundation for the theoretical research and application of cold-adapted enzymes.

Cold adaptation: gut bacteria can make the difference

If someone told you that in our body we harbour billions of bacteria, surely you would feel mocked, but it's true! There is evidence showing that microbes colonize all the part of our body that are exposed to the external environment (like mouth and skin), with the greater portion of them residing in the gut. All the microorganisms, which are resident in our intestinal tract, are defined by scientists as gut microbiota. Importantly, gut microbiota is not a fixed group of microorganisms, but it may vary in its composition according to several factors e.g. food, age, health, antibiotic use (read also the Break: Collateral damage: antibiotics disrupt the balance in the gut).

In the past twenty years, interest has increased in science for the study of the interplay between the gut microbiota and our bodies. It is now clear that microbiota, also called "the forgotten organ", plays a major role both in physiological and pathological conditions. Gut microbiota has a variety of different functions, among which harvesting energy and providing information for the correct maturation of the immune system. Imbalance in the microbiota community, called dysbiosis, has been correlated with the development of different diseases like autoimmune and allergic diseases, obesity and diabetes1,2. However, the biological mechanisms and the factors that guide the effects of microbiota on the human metabolism are still poorly understood.

Recently, researchers from Dr. Trajkovski's lab described how cold exposure leads to a specific change in the composition of gut microbiota that favours energy absorption. After exposing lab-mice to cold for 10 days, they detected an increase in energy consumption and a decrease in body weight. Unexpectedly, despite the stable energy expenditure and food intake, the loss of fat decreased over time, leading the researchers to investigate the effects of prolonged cold exposure. In particular, focusing on the gut microbiota composition, they were able to observe a shift from "warm microbiota" to "cold microbiota" after 30 days of cold exposure. Interestingly, the transplantation of the "cold microbiota" into mice born without any microorganisms living in or on them (called germ-free mice), was sufficient to induce the metabolic changes needed to make these mice more resistant to cold. The researchers have shown that the above mentioned effects were promoted by the browning of the white fat depots (read also the Break: The colour beige: heating up the fat), in part mediated by the shift in the microbiota composition.

Furthermore, they investigated in detail the effect of cold exposure on the intestine. After prolonged cold exposure, the researchers observed a dramatic increase in intestinal surface area, which improves the mice's ability to get energy from food. This improvement in energy absorption explains the stabilization of the mice's body weight despite the increased energy consumption when exposed to cold. Remarkably, they also observed that one specific species of bacteria, Akkermansia muciniphila, is almost completely absent in the cold microbiota, and its transplantation into mice leads to a full prevention of their ability to enhance energy absorption and increase intestinal surface.

It is becoming clear that the relationship between host and gut microbiota plays a pivotal role in the regulation of both physiological and pathological conditions. In their publication, researchers propose that the co-evolution between host and microbiome may have had a role during periods of increased energy demand, like winter, where changes in the gut microbiota composition were needed to increase the calorie absorption from food. The group of Trajkovski was able to show that the above mentioned increment in calorie absorption is in part due to the expansion of the intestine. Furthermore, one strain from the gut microbiota, Akkermansia muciniphila, was reported to revert some of the benefits of cold exposure, representing the first example of symbiosis able to affect body's energy utilization.

Gut Microbiota Orchestrates Energy Homeostasis during Cold

1.) Cold exposure leads to marked changes in the gut microbiota composition

2.) Cold microbiota transplantation increases insulin sensitivity and WAT browning

3.) Cold exposure or cold transplantation increase the gut size and absorptive capacity

4.) Reconstitution of cold-suppressed A. muciniphila reverts the increased caloric uptake

Microbial functions in the host physiology are a result of the microbiota-host co-evolution. We show that cold exposure leads to marked shift of the microbiotacomposition, referred to as cold microbiota. Transplantation of the cold microbiota to germ-free mice is sufficient to increase insulin sensitivity of the host and enable tolerance to cold partly by promoting the white fat browning, leading to increased energy expenditure and fat loss. During prolonged cold, however, the body weight loss is attenuated, caused by adaptive mechanisms maximizing caloric uptake and increasing intestinal, villi, and microvilli lengths. This increased absorptive surface is transferable with the cold microbiota, leading to altered intestinal gene expression promoting tissue remodeling and suppression of apoptosis—the effect diminished by co-transplanting the most cold-downregulated strain Akkermansia muciniphila during the cold microbiota transfer. Our results demonstrate the microbiota as a key factor orchestrating the overall energy homeostasis during increased demand.

Fungal Cold Adaptation Linked to Protein Structure Changes: Study

Environmental pressure seems to spawn changes in the intrinsically disordered regions of enzymes in polar yeasts, allowing them to adapt to extreme cold.

There is only a certain amount of stress biological structures can withstand before they fall apart. Tissue fluids freeze into ice crystals when exposed to temperatures below −3 °C, for instance, and enzymes break down and become dysfunctional at extremely low temperatures. But there are organisms that are built to thrive in such harsh conditions. Some species of fungi, for instance, can survive the harsh weather in Antarctica, and scientists have spent years trying to figure out how. A study published in Science Advances on September 7 suggests that these polar organisms may have adapted due to tweaks to unstructured regions of their proteins.

The intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) of proteins are the formless, liquidlike parts of proteins that lack the ability to fold into a functional shape and often react with RNA to form naked, or membraneless, cell organelles such as the nucleolus through a phenomenon known as liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS).

See “These Organelles Have No Membranes”

The study shows that yeasts adapted to harsh cold experienced evolutionary changes in IDRs, which change how phase separation occurs. The researchers found that the structure of the IDRs in species adapted to polar regions is different from those in temperate areas.

The researchers stumbled on these differences while studying how transcription occurs in the cold. They were analyzing two primary components of the transcription system of RNA polymerase II multisubunit enzyme—carboxy-terminal domain (an IDR) and Ess1 prolyl isomerase—in five cold- and salt-adapted species of yeast isolated from the Arctic and Antarctica, when they noticed that the species’ carboxy-terminal domain’s (CTD’s) structure was slightly different than that of the model yeast species baker’s yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae).

In baker’s yeast, the CTD consists of a repeating peptide sequence—YSPTSPS—whereas the polar yeasts’ repeating sequences diverge at positions one, four, and seven. Study coauthor Steven Hanes, a molecular geneticist at SUNY Upstate Medical University in New York, says that the repeating sequence is shared across vast clades of life and is nearly identical even in humans, so this divergence in cold-adapted yeasts was “extremely significant.” He and his colleagues were curious about why the polar yeasts’ CTDs manifest such differences and wondered if these CTDs would still function in baker’s yeast.

First, Hanes and colleagues deleted the gene that codes the CTD of baker’s yeast but kept the CTD intact by retaining the plasmid that expresses the enzyme Rpb1 (a subunit of RNA polymerase II), which kept the host cell alive. Next, they cloned a gene for polar yeasts’ CTD into a plasmid and transferred it into baker’s yeasts. They did this to test whether the divergent CTD would work when paired with the structured region of RNA polymerase II in baker’s yeast. The procedure was carried out at 18 °C and 30 °C to determine the effects of colder temperatures.

Hanes explains that if the cloned CTD gene are compatible with the host, they will push out the original plasmid from the host’s cell in favor of the new one. The degree to which the originals are lost will give an estimate of the cloned plasmid’s degree of compatibility with the model species.

The baker's yeast replaced its own plasmid with that of the various polar yeasts fairly well at 30 °C. But at 18 °C, the baker’s yeast containing CTDs from the Arctic fungi Wallemia ichthyophaga, Aureobasidium pullulans, and Hortaea werneckiilost only 0.2 percent, 13.6 percent, and 21.5 percent, respectively, while those that contained CTDs of the Antarctic fungi Dioszegia cryoxericaand Naganishia vishniacii did not lose any of the original plasmids. In contrast, the control lost 58 percent and 87 percent of the original plasmid at 18 °C and 30 °C, respectively. The researchers report that the CTD from polar yeasts did not work in baker’s yeast at 18 °C.

See “How a Bacterium Manages to Reproduce During Famine”

Hanes says that he suspected the differences may stem from the mechanisms of LLPS, as a previous study revealed CTDs can undergo the process. So the team checked if the CTDs from the cold-adapted yeast can also undergo this phenomenon.

The researchers bound polar CTDs with purified proteins in a test tube and checked for LLPS by observing the cloudiness of the solution—evidence that LLPS occurred—at different temperatures and salinity levels. Hanes and his team observed that the CTDs of these polar yeasts do undergo phase separation, but they do so differently than baker’s yeast. They noticed that the CTDs of species that were most compatible with S. cerevisiae at 18 °C exhibited high LLPS, while those that were not compatible showed none. The researchers attributed these differing properties to the divergence in the CTDs’ amino acid sequence, and they hypothesize that this divergence might promote cold and salt tolerance in the polar species.

Hanes says that the intrinsically disordered regions in the protein with more variable sequences are very adaptive to “selective pressures that would change the biophysical properties of how the proteins sort out within cells.” And this adaptation can change how, when, and where they undergo phase separation.

“We know that stress can induce phase separation by certain proteins, but what we are suggesting is that environmental tuning of phase separation allows organisms to tolerate temperature and other extreme conditions,” says Hanes.

Amy Gladfelter, a cell biologist at the University of North Carolina who studies phase separation and didn’t work on the new study, says that the results are “really suggesting that by looking at natural variation and . . . at how free-living yeast may adapt to extreme temperatures and also extreme salinity, [the research team] can find evidence of adaptation in sequences that are important to drive phase separation.”

Hanes tells The Scientist that the study has uncovered more questions than answers, but the team intends to resolve most of them, including the exact mechanism through which phase separation properties confer environmental tolerance, because this could help other microorganisms to survive harsh and changing climate conditions.

The Role of the Gut Microbiota on the Beneficial Effects of Ketogenic Diets

A ketogenic diet affects the gut microbiota and with it also multiple domains of human health. A ketogenic diet increases the alpha diversity of the gut microbiota and affects the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio. Moreover, a ketogenic diet is associated with decreases in fecal SCFA and increases in A. muciniphila.

Ketogenic Diets Alter Gut Microbiome in Humans, Mice

Analysis of microbial DNA found in participants' stool samples showed that shifting between standard and ketogenic diets dramatically changed the proportions of common gut microbial phyla Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Firmicutes in participants’ guts, including significant changes in 19 different bacterial genera. The researchers focused in on a particular bacterial genus – the common probiotic Bifidobacteria – which showed the greatest decrease on the ketogenic diet.

To better understand how microbial shifts on the ketogenic diet might impact health, the researchers exposed the mouse gut to different components of microbiomes of humans adhering to ketogenic diets, and showed that these altered microbial populations specifically reduce the numbers of Th17 immune cells – a type of T cell critical for fighting off infectious disease, but also known to promote inflammation in autoimmune diseases.

While there is ongoing research on the effects of a ketogenic diet on the gut microbiome and studies on cold-adapted microbiomes in different environments, the direct parallels between the two are not well-documented.

Now, can you do this for yourself:

ASK ANYONE ON A KETOGENIC DIET WHEN THEY LAST HAD COLD-LIKE SYMPTOMS

WHO loves games —>> The game of 219 virus species that are known to infect us <<— Find out what hit you

Designing a game is not easy. No one will show interest if it is not exciting. Games that keep players engaged draw success with addictive rules and rewards. The setup should offer various areas for players with different interests, such as strategy, investigation, drama, fun, and routine.

.